NEW BOOK NEW BOOK NEW BOOK NEW BOOK

As the pictures show; my office looks a bit messy, however, it’s all organized now. I have been tied to this place for the entire winter for 7 days a week and I am now happy to announce that my new book, which I wanted to publish for so many years, is now ‘really’ going to happen! The title is;

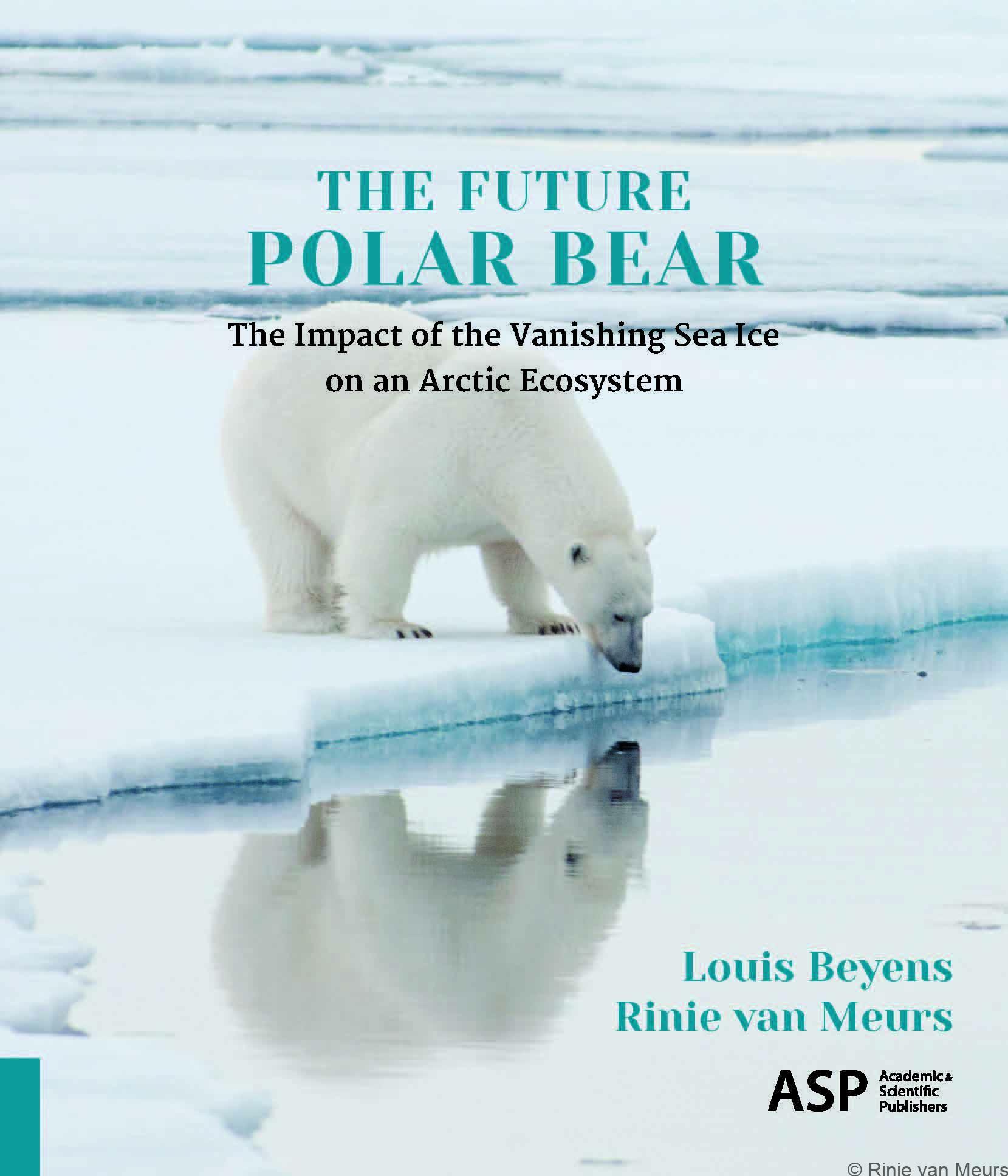

The Future Polar Bear, the Impact of the Vanishing Sea Ice on an Arctic Ecosystem.

What is this book about? Together with, Louis Beyens, (Professor Emeritus at the University of Antwerp, Belgium) we wrote about the impacts of the declining Arctic sea ice on the ecosystem as a whole. The media often creates the image among the public that we (only) lose the Polar Bear if the sea ice keeps shrinking as predicted; we explain that there is much more at stake.

Furthermore, the book is a ‘hybrid’ of Arctic science, geography, biology, and climate change. We take the reader through the Arctic food web, from the moment the ice is formed and subsequently colonized by ice algae we travel up through the trophic levels like zooplankton, fish, seabirds, seals, and we end with the top predator; the Polar Bear. The book is not ‘doom and gloom’; it explains all the biological aspects of the ecosystem, interwoven with (possibly) negative effects of the declining sea ice. Also, if you remain unsure about climate change science, our book teaches you and everyone, about what is happening in the Arctic, while showing you the beauty and richness of this food web and ecosystem.

Our book features many photographs, maps, and illustrations of many of the sea-ice animals, from plankton to Polar Bears, to create an attractive visual experience for the reader. We seek to entertain as well as to inform the reader. Our book is 240 pages and at a trim size of 24×29 cm (9.5×11.5 in.).

It will be published by ASP Editions (Academic & Scientific Publishers) in Brussels, Belgium. (May 20th 2019) https://www.aspeditions.be/nl-be/book/the-future-polar-bear/16554.htm (for English go to top right of opening page). It will also be available at Amazon.com later this year, exact date will be announced.

Thank you for reading this.

Rinie

Another record!

As some of you may know, on an ice breaker to the Geographical North Pole in 2001, together with John Splettstoesser, I spotted the northernmost Polar Bear ever seen! The bear was at 89º 46’ 5” North, which is 13 nautical miles, or 24 km, from the North Pole. This is the farthest north sighting of a Polar Bear recorded to date. The record sighting was reported in 2003 in Arctic 56: 309.

Yet, I am fortunate to witness another record! Please find below the abstract of a paper by Ian Stirling and myself, about a record dive by a Polar Bear that I observed August 19, 2014, during the bear’s aquatic stalk in sea ice, north of Spitsbergen. Polar Biology accepted our paper for publication, however I must wait a year before I can put the full content on my web site. I will keep you posted. Meanwhile, please see the abstract which gives you essential information about the exciting event we observed.

Longest recorded underwater dive by a polar bear

Ian Stirling1 • Rinie van Meurs2

The maximum dive duration for a wild polar bear (Ursus maritimus) of any age is unknown, and opportunities to document long dives by undisturbed bears are rare. We describe the longest dive reported to date, by a wild undisturbed adult male polar bear. This dive was made during an aquatic stalk of three bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) lying several meters from each other at the edge of an annual ice floe. The bear dove for a total duration of 3 min 10 s and swam 45–50 m without surfacing to breathe or to reorient itself to the locations of the seals. The duration of this dive may be approaching its maximum capability. Polar bears diverged from brown bears (Ursus arctos) about 4–500,000 years ago, which is recent in evolutionary terms. Thus, it is possible that the ability to hold its breath for so long may indicate the initial development of a significant adaptation for living and hunting in its marine environment. However, increased diving ability cannot evolve rapidly enough to compensate for the increasing difficulty of hunting seals because of the rapidly declining availability of sea ice during the open water period resulting from climate warming.

Searching for Polar Bears in Spitsbergen with World Renowned Scientist

Last year, 2015, we were privileged to have Dr. Ian Stirling with us on board the “M/V Ortelius for our “Polar Bear Specials” in Spitsbergen. Ian is one of the most prominent Polar Bear researchers in the world. He is an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta. Ian has authored or co-aut hored more than 300 scientific articles. He has studied Polar Bears throughout the Canadian Arctic for over 40 years, with the Canadian Wildlife Service. In recognition of his research, he has won several awards including being appointed as an Officer in the Order of Canada and elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

hored more than 300 scientific articles. He has studied Polar Bears throughout the Canadian Arctic for over 40 years, with the Canadian Wildlife Service. In recognition of his research, he has won several awards including being appointed as an Officer in the Order of Canada and elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

He is the author of four books for the public including; “Polar Bears, The Natural History of a Threatened Species”, considered the definitive work on the biology of the Polar Bear.

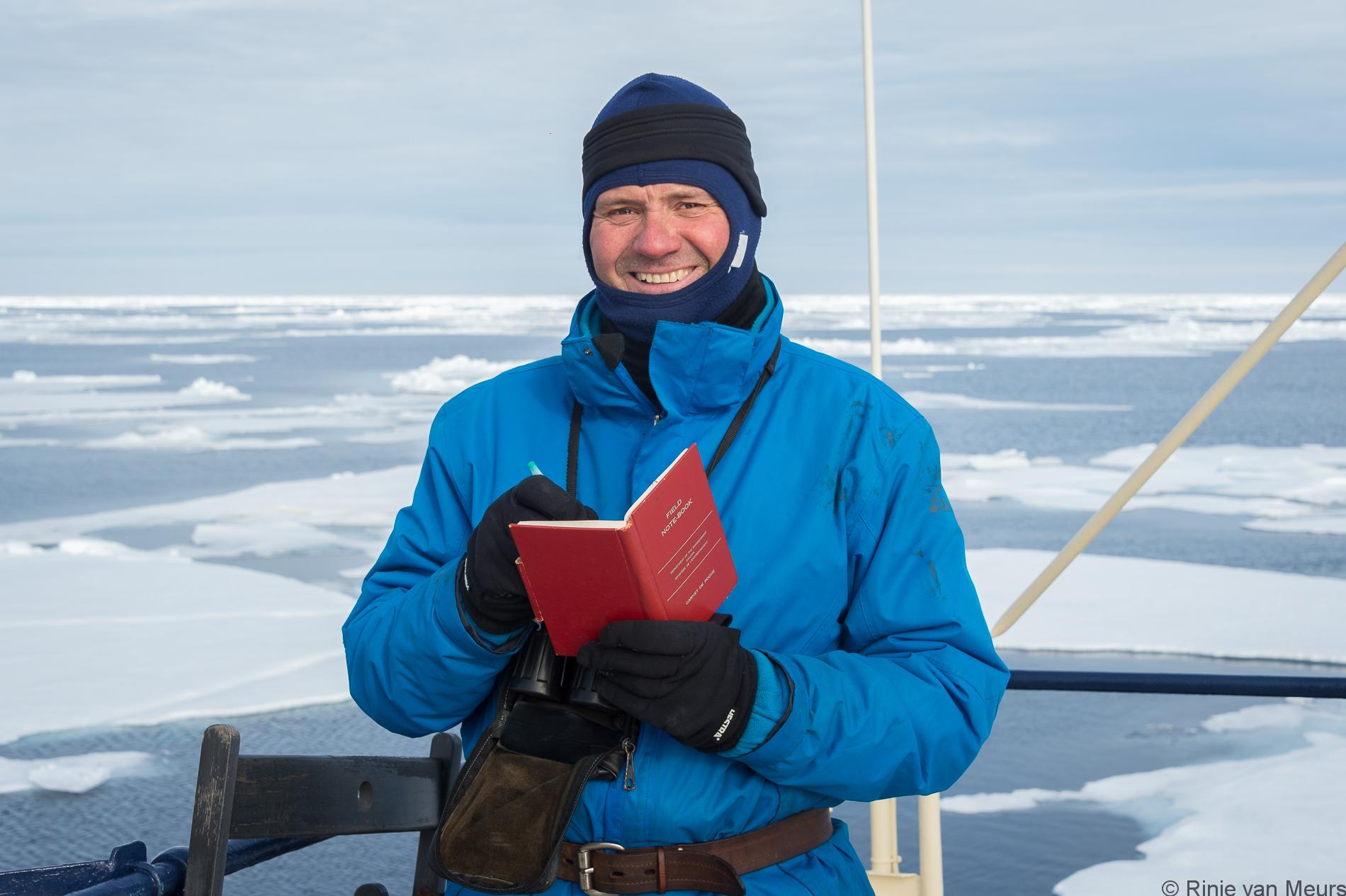

The picture below is of Ian Stirling and myself on board “M/V Ortelius” in the sea ice north of Spitsbergen. For several weeks, Ian and I spent many hours together on the outside top deck scanning and of course talking a lot about Polar Bears. Besides being a world renowned scientist, Ian is also a fantastic person to have on board with the passengers and a “heck of a guy” to work with.

Me with my field note book from the; “Department of the Environment Canada”. Ian also convinced me to take more detailed notes of Polar Bear behavior in the field…oh well sea ice. He sent me this book as a present and despite freezing my fingers off, I kept notes of every single bear observation this last summer, exactly as the master told me J.

Short life story of a female Polar Bear in Spitsbergen

Last summer (2016), I found a rather skinny Polar Bear in Smeerenburgfjorden, on the northwest corner of Spitsbergen Island. When we approached closer with the ship, I could see that it was a female with a big number 74 on her back. I knew by this ‘mark’ that she had been captured not long before, in spring. Scientists give bears after they have been handled, a number so they recognize the individual animal if spotted again, that the bear has been captured already in a given season (the paint doesn’t last long). The number tells them which Polar Bear it is, so it provides them some information about their movements.

Later in the season I worked with a friend of my, Arjen Drost ( www.natureview.nl) and was informed that he managed to get a good picture of bear number ‘74’ and he had also contacted the Norwegian Polar Institute for her details. It turned out that she was 12-13 years old, captured 7 times since 2007 and always in the same area. Last time she was handled was April 2016 and her satellite transmitter (collar) was taken off. The collar left a mark in the fur, which is still visible in the picture below.

In 2014 she had one COY (cub of the year, born in winter 2013-14) with her and spent most of that summer in the Raudfjorden area scavenging on dead dolphins. I actually happen to see her there a number of times that summer and managed to get a nice picture of her (see picture below). Last time when I saw her that year was in late September. The sea ice had come south and was not far, (for a Polar Bear) so it is very likely that she managed to get to the ice and resume hunting for seals and hopefully her cub survived. However, the cub’s fate most likely never be known. (See my picture here below with her cub)

Polar Bears seem to use two distinctive strategies in search of food; there are the “home stayers” and the “travellers”. Home stayers use their local knowledge to exploit food sources, usually in fjords on the remaining fast ice hunting for Ringed Seals in spring and later in summer near glacier fronts, hunting for Bearded Seals. However this strategy works not very well when in a spring the ice situation in the fjords are poor and the sea ice is too far away, then you simply become stuck on land where food is scarce. However, on the other hand they preserve lots of energy by not travelling much. The travellers spend a lot more energy (sometimes thousands of miles in a summer) by searching the sea ice for that restaurant “all you can eat” and when they do, they regain body fat reserves very quick. Of course, some bears live a little bit of both strategies.

Our female, number 74, was skinny this summer because there was hardy sufficient fjord ice during this last spring (2016). The sea ice remained far north of the Spitsbergen coast whole winter and never came close enough for the home stayers to reach it as an alternative. That’s why number 74 was very thin this summer. Let’s hope we’ll see her again next year. I will keep you updated.

After 29 years my first Polar Bear triplets! Yahoo!

The sea ice conditions last spring/summer (2018) were rather interesting around Spitsbergen. At first, temperatures at the Geographical North pole were in the middle of the winter higher than ever recorded. When I checked out the sea ice situation (using ice charts) at that time around Spitsbergen, I noticed that the main ice edge was still very far north of the islands. I kept my fingers crossed for the Polar Bears and especially wondered how the pregnant females would have made it to land for denning. Then suddenly, there was a steep temperature drop and this remained for a long period of time. The result was that the sea ice “migrated” steadily south, right up against the coast of Spitsbergen. There was still so much ice until the second week of July, that finding Polar Bears was a bit difficult because we couldn’t reach the east. The eastern parts of the archipelago tend to have higher Polar Bear densities than the west. Nevertheless, we managed to find a few good bears on every trip. For instance on a trip with the ship “Freya”, we found this mother and twin coys (cubs of the year) in the Björnsundet (Bear Sound). We worked with her from the zodiacs (see picture) for almost two hours! She was an amazing mom.

When the ice receded further east later in July, we hit the Polar Bear jackpot! This was on our 20 day Polar Bear trip with the ship “Malmö“. After several good bears, including mom and cubs, we found a dead Narwhal in the north east with six bears feeding on it. We stayed for two days at the carcass. However, we were absolutely stunned when we found yet another dead Narwhal north of Kong Karls Land in the east. This time there were no less than 11 bears around when we arrived! We parked the ship in a solid ice floe and we just sat there, observing and photographing Polar Bears all around the ship. In total we counted more than 25 different bears which came around to feed in this restaurant “all you can eat”. This bonanza also attracted two different mothers with twin coys, but they were reluctant to join the feast with all these big males around. Instead they came checking us out on the ship, providing us with great photo opportunities!

When the ice receded further east later in July, we hit the Polar Bear jackpot! This was on our 20 day Polar Bear trip with the ship “Malmö“. After several good bears, including mom and cubs, we found a dead Narwhal in the north east with six bears feeding on it. We stayed for two days at the carcass. However, we were absolutely stunned when we found yet another dead Narwhal north of Kong Karls Land in the east. This time there were no less than 11 bears around when we arrived! We parked the ship in a solid ice floe and we just sat there, observing and photographing Polar Bears all around the ship. In total we counted more than 25 different bears which came around to feed in this restaurant “all you can eat”. This bonanza also attracted two different mothers with twin coys, but they were reluctant to join the feast with all these big males around. Instead they came checking us out on the ship, providing us with great photo opportunities!

When the carcass was finished we collected the 2 meter Narwhal tusk for the museum in Longyearbyen.

We stayed in total four full days! We had fantastic weather and we were surrounded by the ice pack with Polar Bears all over the place! Wow what an experience!

However, if this was not enough yet, on our way back out of the ice we found a mother with triplet yearlings! Triplets are rare and certainly yearlings, as usual one young cub dies in the first summer. She must have been a good hunter/mother to manage this big family. These were my first triplets in 29 years!

On another note, only one of the triplets had ear tags, (or the other ones were invisible, we will never know) so it is likely that this cub was adopted from another female, already at young age. This happens sometimes during close encounters on the ice with other families, where a cub walks off with the wrong mother. So probable not genuine triplets but certainly very exciting!

What a way to end the season. It couldn’t be better!

One of our passengers on this extraordinary Polar Bear trip was Graham Boulnois from the U.K. Please check out his website for video clips of this special voyage: www.wildlifeaction.co.uk

The ecological and behavioral significanceof short-term food caching in polar bears (Ursusmaritimus)

Ian Stirling, Kristin L. Laidre, Andrew E. Derocher, and Rinie Van Meurs

Abstract: The paucity of  observations of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus) caching of food (including hoarding, i.e., burying and remaining with a kill for up to a few days) has led to the conclusion that such behaviour does not occur or is negligible in this species. We document 19 observations of short-term hoarding by polar bears between 1973 and 2018 in Svalbard, Greenland, and Canada. Short-term hoarding appears to be influenced by size of the kill and its remaining energetic value after the first meal has been consumed. Fat and meat from smaller seals, such as pup or yearling ringed seals (Pusa hispida), are largely devoured immediately, leaving little to hoard. Carcasses of adult ringed seals, harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus), and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) may be covered with snow to reduce the chance of kleptoparasitism by another bear or other scavengers visually detecting a dark spot on the ice, while the hoarding bear lies nearby. Hoarding of other species, such as beluga (Delphina pterusleucas) (calves or parts) or other polar bears, appears opportunistic. We review differences in caching, including short-term hoarding behavior between polar bears and brown bears (U. arctos), and hypothesize about factors that may have influenced their evolution.

observations of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus) caching of food (including hoarding, i.e., burying and remaining with a kill for up to a few days) has led to the conclusion that such behaviour does not occur or is negligible in this species. We document 19 observations of short-term hoarding by polar bears between 1973 and 2018 in Svalbard, Greenland, and Canada. Short-term hoarding appears to be influenced by size of the kill and its remaining energetic value after the first meal has been consumed. Fat and meat from smaller seals, such as pup or yearling ringed seals (Pusa hispida), are largely devoured immediately, leaving little to hoard. Carcasses of adult ringed seals, harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus), and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) may be covered with snow to reduce the chance of kleptoparasitism by another bear or other scavengers visually detecting a dark spot on the ice, while the hoarding bear lies nearby. Hoarding of other species, such as beluga (Delphina pterusleucas) (calves or parts) or other polar bears, appears opportunistic. We review differences in caching, including short-term hoarding behavior between polar bears and brown bears (U. arctos), and hypothesize about factors that may have influenced their evolution.